Science

Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Kimmerer

“Despite our fears of falling, the gifts of the world stand by to catch us.” I started each morning this spring with a few pages from this poetic book by Robin Kimmerer. Robin is a professor of environmental biology and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and the combination of science, indigenous wisdom, and sheer love of our natural world shines through on every page. Whether you swim in a sea of digital data or in a pond hidden deep in the woods, you will find beauty and wisdom here. (Note: for video, see Robin’s Bioneers talk. For Audio, listen to the terrific conversation with Krista Tippett at OnBeing.)

The Hidden Life of Trees, by Peter Wohlleben

The best science is something very close to magical, and the best science writing is something very close to poetry. Many of you have already heard me wax on about the wonders of mycelium, so this book is a dream come true – lots of the terrific recent science of forest networks, bundled up in a lovely package. As I read this book, I kept thinking of the contrast between the redwood forest where I studied biomimicry and the sad, single redwood specimen that lives in the Boston Public Garden, completely disconnected and out of place. It’s not an artistic, unscientific leap to consider forests as a type of community, with some of the same attributes of human communities – Wohlleben illuminates these parallels convincingly, in prose that is both lyrical and logical.

Summer World, by Bernd Heinrich

I’ve taken to keeping a volume of Bernd Heinrich’s always at hand – his books are like great short stories of nature, readable a few pages at a time or in big long gulps, all connected yet able to stand on their own as well. Perhaps this is because Heinrich is writing so beautifully about our natural world and its wonders – poetry plus science, fused together in the most wonderful way. He doesn’t skip the less- pretty stuff – insects and frog reproduction feature prominently – but these parts are gorgeous, and fascinating.

The Botany of Desire, by Michael Pollan

Taken at face value, this Pollan book is a solid offering: neat cases studies of a few key plants and their histories over time. But pulled up to a slightly more abstract level it’s even more interesting, as it addresses the intersection of human society and the natural world, and examines desire as one form of demand – themes applicable to valuations of all sorts.

Letters To A Young Scientist, by E.O. Wilson

"He talks about science, sure, but he also talks about curiosity, and trust, and truth. Honeybees will know that I am a big fan of E.O. Wilson, and I am also a big fan of learning from folks who have been engaged in any endeavor for a good long while. Talk with an outgoing CEO who has spent decades at one company and is in a reflective frame of mind, and I guarantee it will be one of the most satisfying meetings you’ll ever have. As a junior analyst, I established the “longer than I’ve been alive” principle when I met Stan Rubin at Merrill Lynch, who had covered General Electric longer than I’d been alive. He was the only person on Wall Street who could talk about Reg Jones (CEO before Jack Welch) from direct personal experience, and a huge source of wisdom -- as long as you didn’t consider “wisdom” to be micro-analysis of the last quarter’s tax rate. Eventually I extended this experience with Stan into a more general rule: if you’ve done something – anything - longer than I’ve been alive, I want to learn about it from you. Happily E.O. Wilson is in this category – and I am grateful to hear anything that he has to say."

H is for Hawk, by Helen Macdonald

I tore through this terrific book during summertime, and kept thinking, “this is a wintery novel – it should be read under lots of blankets, or by a fire as the sun sets before supper’s even been served.” Well, surprise – it’s not a novel at all! Helen’s nonfiction account of hawk training is mesmerizing, and it swoops in and out of the narrative of her own life like the bird at its center. An interesting companion to My Kitchen Year, noted above.

Landmarks, by Robert Macfarlane

Do you remember learning that there are thirty-two words for rain in Ireland, or sixty-three ways to say “dark” in Finland, or eighteen versions of “hot” in Thailand? I’m not sure how accurate these individual claims are, but the idea that language reflects the world around us – and values it by doing so - is a powerful one. Landmarks sets out to catalogue the language of landscape in Britain, “to sing the world back into being”. Fa-la-la! I find myself saying these magical descriptive words out loud as I read, as if they are incantations. Which, perhaps, they are.

Arrival of the Fittest, by Andreas Wagner

As in many fields, attention in evolution has been disproportionally focused on one piece of a fascinating puzzle: natural selection. This piece is vital, of course, but Wagner notes that natural selection preserves innovations; it does not create innovations. This book seeks out the puzzle piece of innovation creation, the part before natural selection (hint: it’s not just chance). In exploring this library of natural components, Wagner does not hesitate to note the mega-questions that remain, painting a terrific picture of the broader landscape that is yet to be mapped.

Survival of the Beautiful, by David Rothenberg

This book had me hooked from the opening sentence, when the author describes coming across a bowerbird’s creation in the Australian rainforest. The book is a delightful cris- crossing of disciplines, with plenty of illustrations from each. Rothenberg is a musician, philosopher, and naturalist, so his perspectives form a great complement to the other points of view in our pod of evolutionary readings (I’m eager to explore his latest, Bug Music, too). Lest you think that beautiful = wishy-washy, consider the wisdom of Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann regarding beauty in physics ((http://go.ted.com/bGNW)). Rothenberg concludes, “The beautiful is the root of science and the goal of art, the highest possibility that humanity can ever hope to see.” Well worth considering as the sun sets over the mountains.

Seeds, by Wolfgang Stuppy

All three of these books are full of gorgeous images, and all remind us of the intertwining of beauty and function that exist throughout the natural world. Stuppy is the expert on seeds and fruit from Kew Gardens, and Cedric Pollet is a botanical photographer who has focused on studying bark since 1999 (no kidding). The microscopic-level photos of in seeds and fruit are just stunning, and Bark won the Redoute award for most beautiful book – maybe this is all you need to know. Think seeds are all alike? How can one be as huge as 20kg or as small as a tiny mote of dust? Think you don’t care about bark? Tell me that as you uncork your wine, or dust your latte with cinnamon.

Dark Matter & The Dinosaurs, by Lisa Randall

Randall is a theoretical physicist and professor of Science at Harvard, and I admire that, like many terrific scientists, Randall is eager to acknowledge all that we don’t yet understand. You have got to love a person who hears the Beatles lyric “Got to be good looking, because he’s so hard to see” and relates it to dark matter and the extinction of the dinosaurs. A more in-depth review of the book can be found from BrainPickings’ Maria Popova here: https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/11/28/dark-matter-and-the-dinosaurs-lisa-randall/ And a terrific OnBeing podcast with Randall can be found here: http://www.onbeing.org/program/lisa-randall-dark-matter-and-the-astounding- interconnectedness-of-everything/8100

Bio-Design, by William Myers

This book is beautiful – chock full of projects that illustrate “the hybrid frontier”, where living organisms are directly integrated into design. The author seems to reflect a serious misunderstanding of biomimicry in the framing of his own focus area (it is not “beyond biomimicry”, but rather fundamentally different from it). Still, the projects featured are stunning in their aesthetics, and challenging in some of their approaches – how much can we “engineer” biology before it is un-natural? A great impact on the reader – you are left feeling equal parts inspired and freaked-out.

A Crude Look at the Whole, by John Miller

As our professions and fields of study have become more specialized, it’s become harder and harder to see the whole. So much time and effort in investing, for example, is spent examining the “leaves on the trees”: we can describe each vein, each rib, each cell. But can we describe the whole tree? Can we even see that we’re in a forest? Miller’s central premise is that it’s helpful to look at the whole, that in doing so we see certain patterns that cannot be revealed up-close. The book is a great introduction to some fundamental concepts of complex systems, which Miller has helped to pioneer through his work with the Santa Fe Institute and Carnegie Mellon. Plus he’s really into ants and bees and slime molds, so you know he’s cool.

I Contain Multitudes, by Ed Yong

Ed Yong is one of the best science writers around, and there is nothing more fascinating than microbes – except maybe fungi, which are fascinating for some similar reasons. If you want to better understand the tiny world that surrounds and supports (and maybe controls) the more visible world around us, there is no better resource than this. It leaves you feeling inspired and humbled in equal parts, one of my favorite combinations. You might also enjoy Ed’s ongoing work for The Atlantic, and yes, he too has a TED talk, featuring zombie roaches– one of my all- time favorites.

The Soul of an Octopus, by Sy Montgomery

Can it be? Two books about the brilliance of cephalopods? Montgomery’s is a friendly tour of octopus awesomeness, while Godfrey-Smith looks at the octopus as an entrée to deeper philosophical questions about the nature of mind. Both are fascinating and engaging, though be warned, you might not ever be able to eat calamari again.

Woolly, by Ben Mezrich

When I first heard de-extinction explained, it was by Stewart Brand at the TED conference, and at the next coffee break I heard a guy exclaim with glee, “it will be just like Jurassic Park!” I turned to ask him if he’d actually seen that movie, but he was already gone. Questions persist about consequences of de-extinction, but a number of the world’s most talented scientists are working on exactly that, including George Church, whose research is at the heart of the Wooly story. If you are interested in advances in genetics, how the mammoths might save us from climate change, or how a technical scientific story can turn into a page-turning thriller, this is the book for you.

The Wonder of Birds, by Jim Robbins

Robbins is like the best party host, introducing us to (as the title accurately promises) the wonder of birds, sharing terrific stories, and emphasizing the points of connection between our species and theirs. The next time someone calls you a birdbrain, you will just beam and say, thank you.

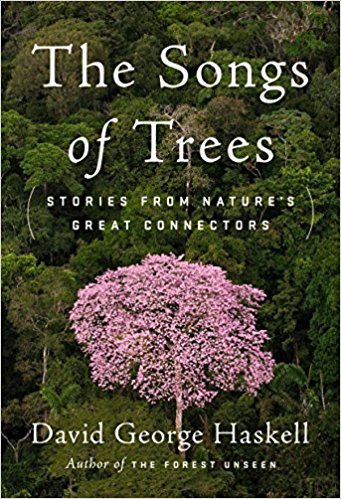

The Songs of Trees, by David George Haskell

If you dig mycelium (pun intended), this book will knock your socks off. Here is a much more detailed summary from Maria Popova of Brainpickings.